---Nablus Soap Production: The Decline of an Ancient Heritage by Véronique Bontemps from The Interactive Encyclopedia of the Palestine Question

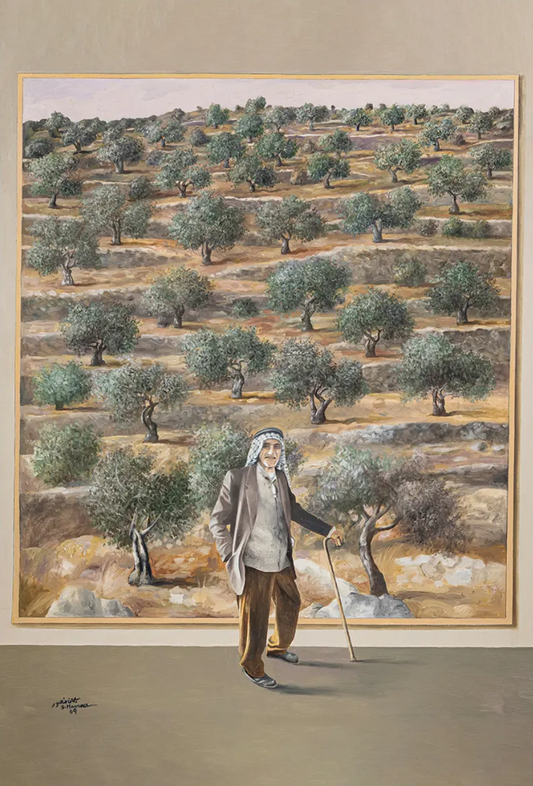

The production of soap is a very old tradition in the Middle East: it is based primarily on the production of olive oil. At first a domestic production, the soap industry developed in urban centers: the most famous are Aleppo in Syria, Tripoli in Lebanon, and Nablus in Palestine. Throughout the Ottoman period, big families of the urban bourgeoisie acquired the main soap factories located in the city center of Nablus. In the nineteenth century, the soap industry became the dominant economic sector of the city: owning a soap factory became a symbol of wealth, prestige, and urban belonging.

Process of Making Soap

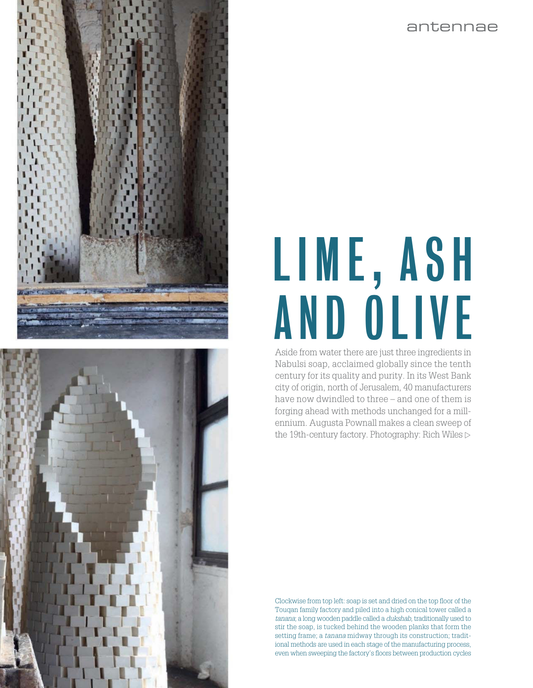

The few Nablus soap factories that have remained operational follow more or less the same manufacturing process (except for some minor changes) that was developed two centuries ago. It is a five-step process—cooking, laying, cutting, drying, and packaging—supported by four different teams of workers.

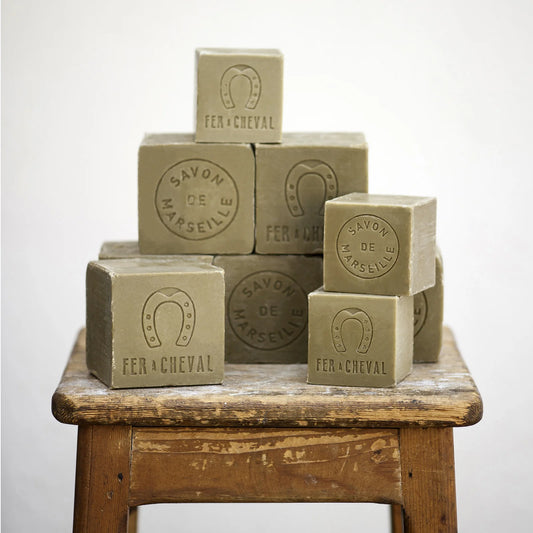

At the ground floor of the soap factory, olive oil (the main ingredient) mixed with caustic soda and water is placed in a large bowl (halla) and “cooked” for three days. (In the first half of the twentieth century, caustic soda, imported from Alexandria and Europe, replaced the qeli, a plant turned into ashes.) Under the tank, a boiler helps the process of saponification. Once the mixture is ready, the head of the team tastes the soap or crumbles it on his hand to check its texture. Then porters carry the mixture in buckets and pour it on a designated section of the first floor (mafrash), where it dries for a day before being shaped into small cubes, stamped with the brand of the soap factory, and cut by a team of three to four trained workers. A day later, the same workers pile the pieces of soap into pyramids (tananir). The soap then dries for two to three months. Another team packages the soap, wrapping it in a paper with the brand of the soap factory. These workers pack an average of 500 to 1,000 bars of soap per hour.

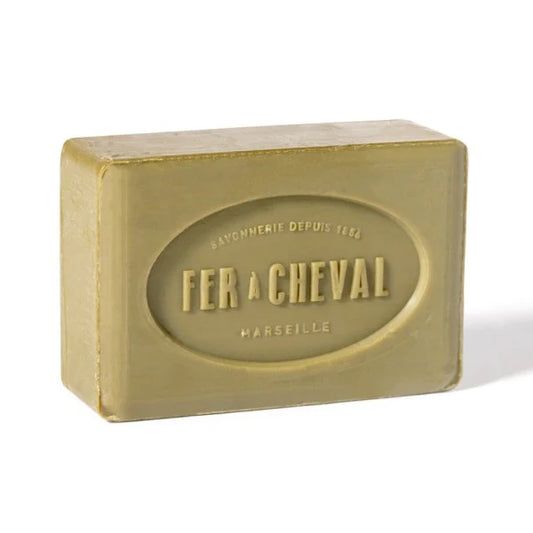

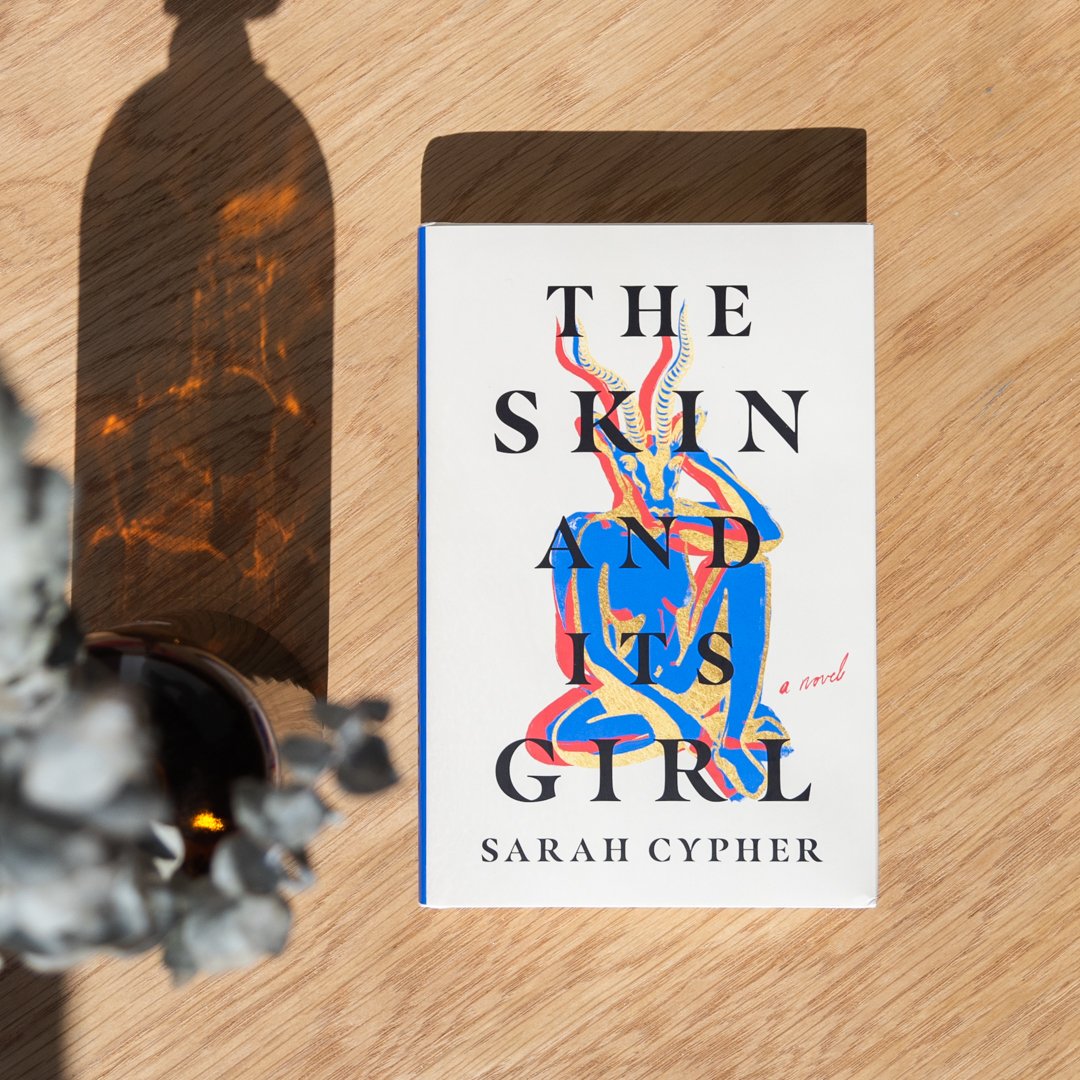

In the heyday of soap production in Nablus, factories were registered companies with brand names and a printed logo on the soap wrapping paper. These brands were often symbols or names of animals; examples include muftahein (the two keys), al-jamal (the camel), al-na‘ama (the ostrich), al-najma (the star), al-baqara (the cow), al-badr (the full moon), and al-assad (the lion). Slogans were added on the packaging such as al-sabun al-Nabulsi al-mumtaz (Nablus soap extra) or al-ma‘ruf (the well-known).

Decline of Soap Production in Nablus before 1948

By 1930, Nablus soap production had experienced its first important setback. Several reasons are usually given for this decline. Egypt and Syria, which were major markets for Nablus soap (especially Egypt), imposed taxes on imported soap. Nablus soap was competing with soap production in Egypt. The label “Nabulsi” attached to the soap was not protected, and as a result, counterfeiting took place. This, coupled with the rise in the price of pure olive oil after the Great Depression of 1929, contributed to raise the price of Nablus soap, making it difficult for Nablus producers to compete with other imported soaps. In addition, Jewish mechanized industry, which also succeeded to obtain customs benefits from the British Mandate, provided local competition.

This first soap crisis reveals the effects, though indirect, of Jewish immigration in the region of Nablus, hitherto relatively protected from the consequences of the Zionist colonization. In general, the absence of a sovereign state capable of controlling borders and taxes meant that Nablus soap was unprotected, while at the same time the British Mandate granted customs benefits to the Zionists traders, and Egypt and Syria were able to impose barriers to protect their local production.

After 1948, the market of historic Palestine closed; so too did the Egyptian market. The East Bank of the Jordan River (Jordan) became the main market for Nablus soap. Soap producers were gradually forced to import olive oil from Syria and Lebanon, and secondarily from Spain and Italy.

Transformation and Final Decline of the Soap Industry

In the 1950s Hamdi Kan‘an, brother-in-law of the soap producer and trader Ahmad Shaka‘a, introduced in Nablus what was called “green soap,” a soap made from jift (solid remains of first press olives, mainly kernels) oil: it was a lower quality soap used to wash the floor and do the laundry. This was a small revolution. Indeed, the exploitation of this new, much cheaper type of oil allowed less wealthy families to rent soap factories and mass-produce household soap. During the 1970s, production of this “second class” soap (which quickly took the generic name of “Kan‘an”), developed rapidly. But it also helped some soap factory workers to become small manufacturers; they rented soap factories in the old city and started to produce soap. At this time, some soap factories tried to mechanize and “develop” the Nablus soap in its form, packaging, and ingredients. Another change (a consequence of the Israeli occupation of 1967) is that all kinds of oils started to be used.

Despite the attempts by some in the soap industry to transform production and adapt to the changing circumstances, the soap industry experienced a steady regression during the second half of the twentieth century, and the first intifada marked the final decline. Small factories producing green soap were already being marginalized by the introduction of detergents and washing machines and cheaper foreign products (like Lux and Palmolive). They could not compete, nor could they afford the new taxes imposed on the soap: their lack of capital prevented them from maintaining their production. Moreover, since the first intifada, soap production became harder to maintain, because the old city was the target of Israeli attacks, and many soap factories thus closed in the 1990s.

In summary, cheaper foreign products as well as the introduction of new consumption patterns brought about the decline of the soap industry in Nablus. Of the more than thirty soap factories in the old city of Nablus, several were damaged by the Israeli invasion of 2002 and two of them completely destroyed; most of the rest have been abandoned or put to other uses. For example, the Arafat soap factory is being developed into a cultural center for children; some producers are using perfumes and mechanization to produce new soaps to keep the tradition of soap making in Nablus alive. Since 2007 only two soap factories have remained functional in Nablus, and they belong to the Tuqan and Shaka‘a families, who keep them as a heritage. These factories export the vast majority of their production to Jordan, taking advantage of long-standing relationships with the distributors on the East Bank of the river and the importance of the Palestinian population in Jordan. From there, a small part of the production is sent to Kuwait and the Gulf.

Selected Bibliography:

Bahjat, Mohammad, and Rafiq Tammimi. Wilayat Bayrut: al-qism al-janubi [The Province of Beirut: Its Southern Part]. Beirut: al-Iqbal Press, 1916.

Bontemps, Véronique. “Soap-Factories in Nablus. Palestinian Heritage (Turâth) at the Local Level.” Journal of Balkan and Near-Eastern Studies 14, no.2 (2012): 279–295.

Bontemps, Véronique. Ville et patrimoine en Palestine. Une ethnographie des savonneries de Naplouse. Paris: Karthala/IISMM, 2012.

Doumani, Beshara. Rediscovering Palestine, Merchants and Peasants in Jabal Nablus (1700–1900). Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1995.

Graham-Brown, Sarah. “The Political Economy of the Jabal Nablus, 1920–1948.” In R. Owen, ed., Studies in the Economic and Social History of Palestine in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1982.

Jaussen, Antonin. Naplouse et son district. Paris: Geuthner, 1927.

Sharif, Husam. Sina‘at al-sabun al-Nabulsi [The Nabulsi Soap Industry]. Nablus: Palestinian Authority: Municipality of Nablus, 1999.

Taher, Ali Nusuh. Shajarat al-zaytun. Tarikhuha, zira'atuha, amraduha, sina‘atuha [The Olive Tree: Its History, Culture, Diseases and Production]. Jaffa, 1947.